Is Glossophobia a Social Anxiety Disorder?

Glossophobia, also known as speech anxiety or public speaking phobia, is a common fear that affects millions of people worldwide. The term originates from the Greek words 'glossa,' meaning tongue, and 'phobos,' meaning fear or dread. And many people ask if glossophobia is a form of social anxiety. To answer this question we need to look at the nature of glossophobia.

Understanding Glossophobia

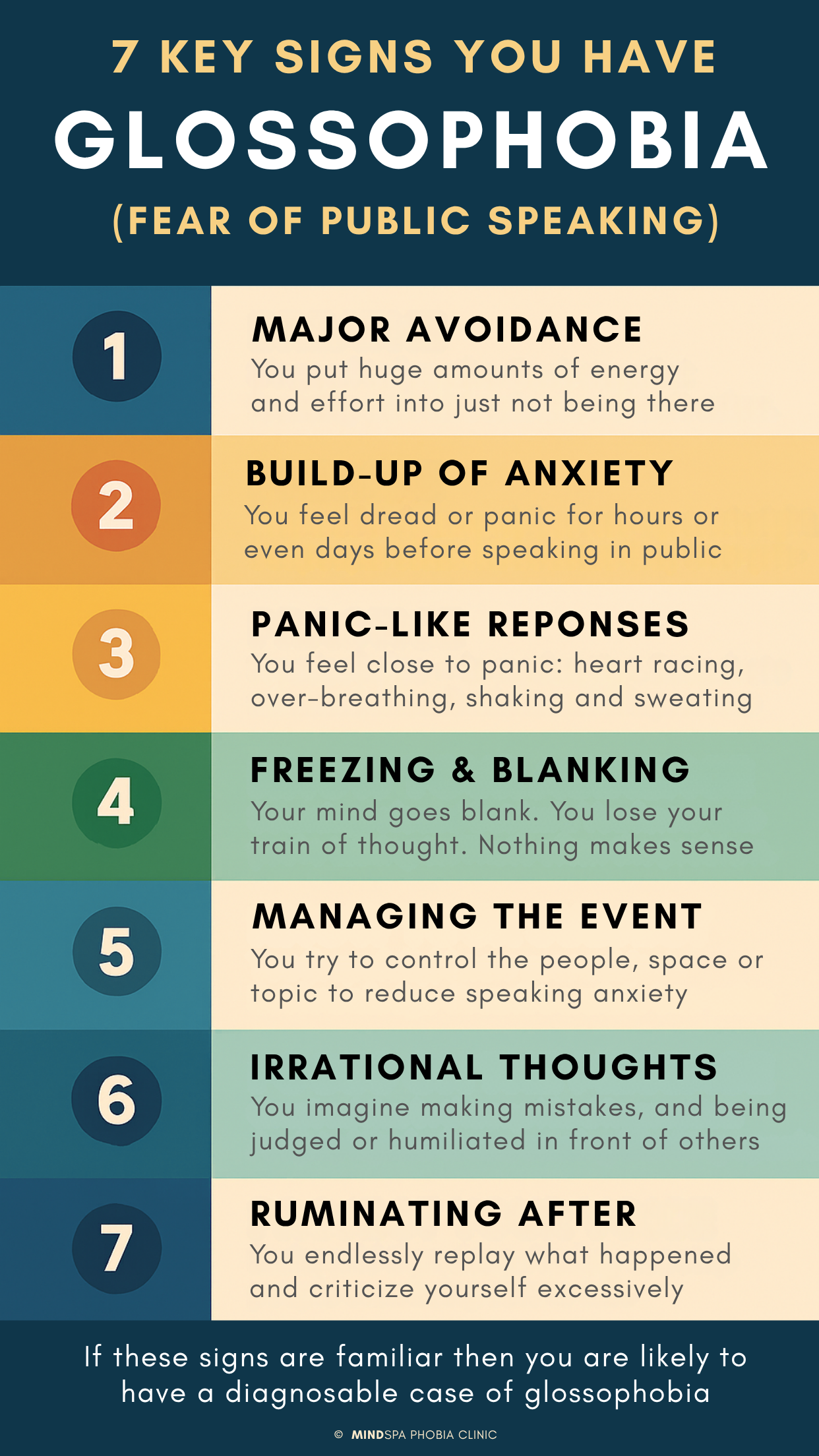

Glossophobia refers to an intense fear or anxiety associated with speaking in public to any group of people. It's not just about feeling nervous before giving a presentation, talking in a meeting or speaking at a social event: it's an extreme form of fear that can cause physical symptoms which include a build-up of dread and fear before speaking and then rapid heartbeat, sweating, trembling, dry mouth and even panic attacks when actually speaking.

Many people don’t like speaking in public but they can do it. On a scale of 0-10 (where 0 is completely comfortable and 10 is having a panic attack) they are probably operating at a 3 or 4. So some anxiety around speaking. But someone with glossophobia will be high on the scale for hours or even days beforehand and then reach 9 or 10 when actually speaking.

People with glossophobia often go to great lengths to avoid situations where they might have to speak in public. This could include declining invitations to events where they might be asked to speak or avoiding jobs that require public speaking.

Social Anxiety and Social Phobia

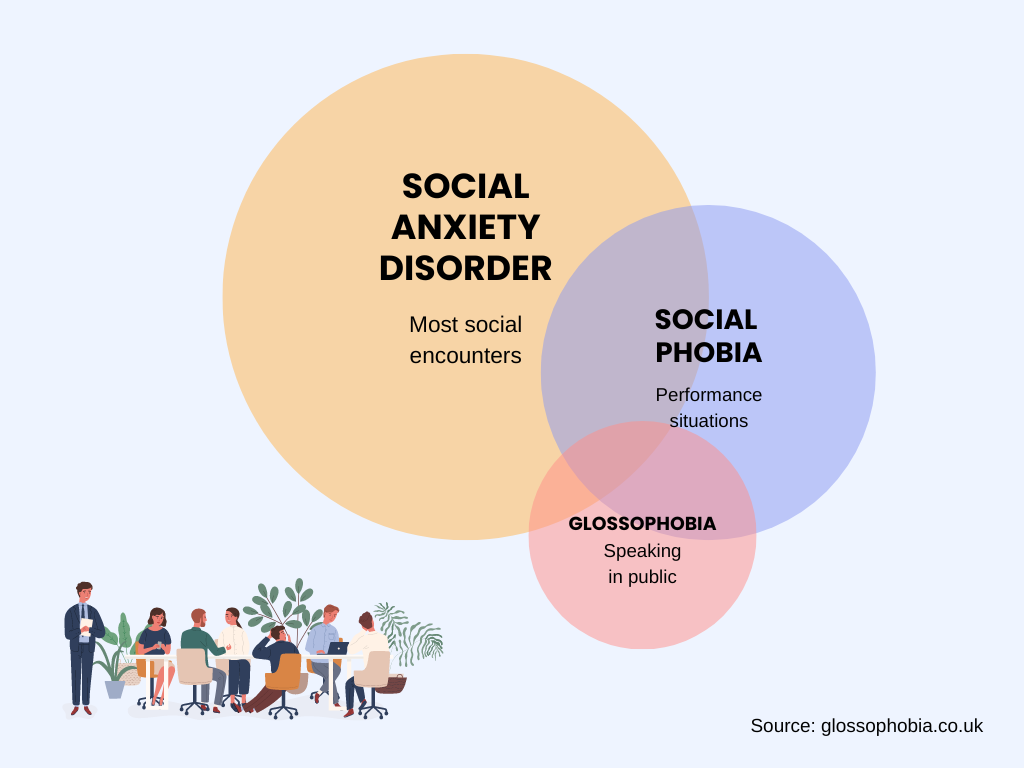

Social anxiety, commonly referred to as Social Anxiety Disorder (or SAD), is an umbrella term for an intense fear of social situations and more generally refers to anxiety experienced when directly interacting socially with others in a broad range of social encounters such as when meeting new people, starting conversations and speaking on the phone.

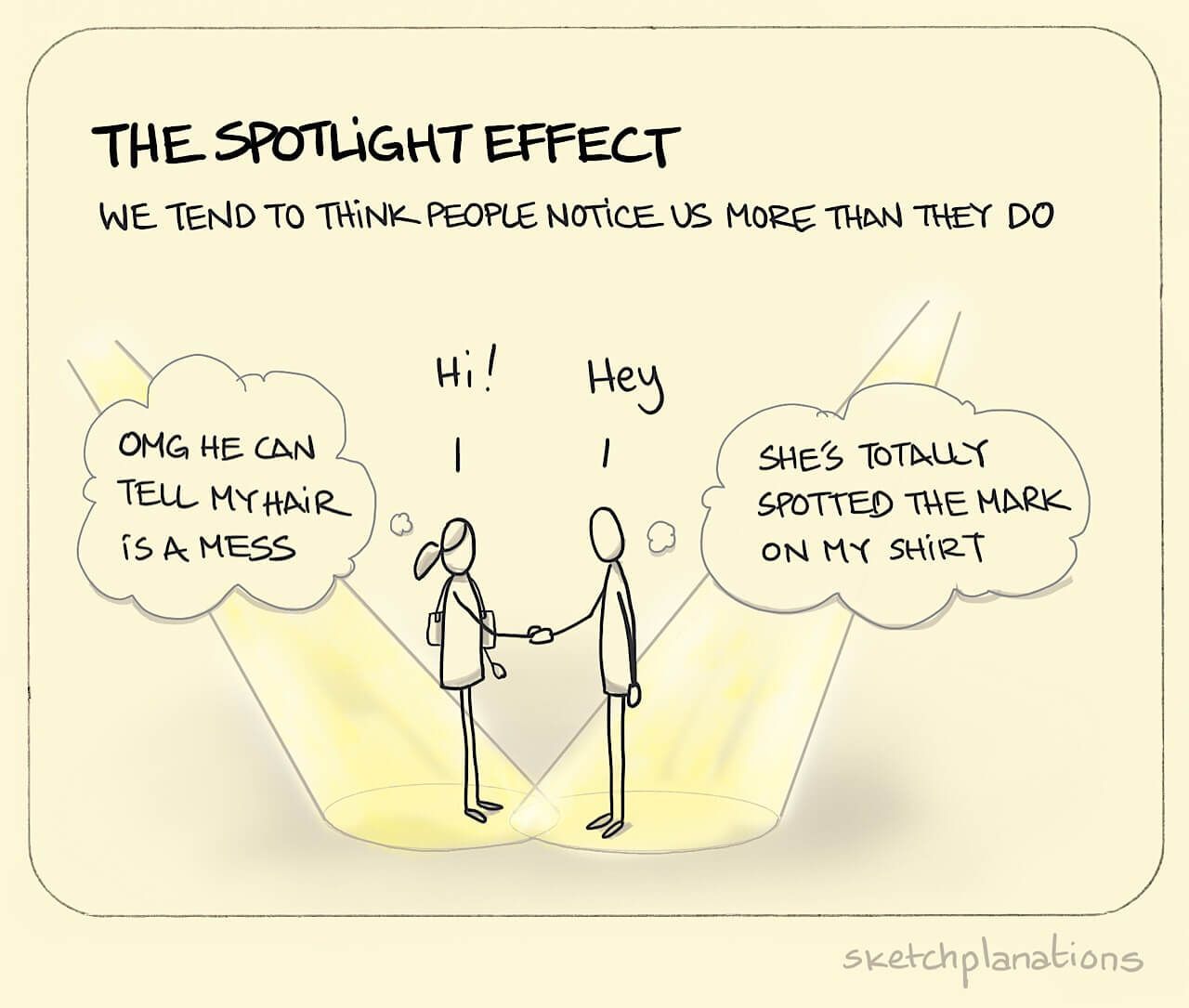

In their giant Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, The American Psychiatric Association’s definition of SAD now includes social phobia which is more specifically associated with performance (like eating in company, using public transport or singing in a choir) where people feel they may be watched, scrutinized and judged by others while in the spotlight (the so-called Spotlight Effect). This obviously includes speaking in public which is why glossophobia is often considered a form of social anxiety.

Glossophobia and Social Anxiety

So while it’s true to say that glossophobia as a form of social phobia falls within the much wider category of social anxiety, it's essential to note that not everyone with glossophobia suffers from social anxiety. Some people may only experience intense fear when asked to speak in public but feel perfectly comfortable and confident in other social situations.

On the other hand, those with social anxiety disorder typically experience fear in a wide range of social situations – not just when asked to speak publicly. Therefore, while there can be an overlap between glossophobia and SAD – and although both can produce the same types of physical, behavioral, and emotional symptoms - they are not synonymous.

So it’s more accurate to say that glossophobia is a well-defined and narrow subset of social anxiety. In fact, most people who get help with public speaking phobia are otherwise confident at work and socially. But when it comes to having to speak in front of a group of people, the same thing doesn’t apply and their phobia kicks in and they feel anxious and frightened. Sometimes the fear may spill over a little into social situations when they feel they are in the spotlight (like suddenly being asked to tell a story to everyone at a dinner party) but they are otherwise fine in social interactions.

Conclusion

So, yes, technically, glossophobia can be considered a type of social anxiety. But this label may be unhelpful. Because most people with a fear of public speaking have simply picked up very specific anxiety responses to usually very specific speaking situations. For them to think they have some form of social anxiety may incorrectly label them with social anxiety and lead them to seek treatment and therapy not specifically directed or relevant to their singular anxiety about speaking in public. Instead, it can be more useful to think of those with social anxiety and glossophobia as falling within these groups:

So if you have a phobia of public speaking, you probably don’t need to worry that, according to a hefty psychiatric manual, you have a big mental health condition called Social Anxiety Disorder. You most likely have a very specific fear of public speaking that can be cured with direct specialist help.

If you are seeking treatment for glossophobia, start here.

Sources

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (5th Edition). Washington, DC.

http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org

Social Phobia Subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey

https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/ajp.155.5.613

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/social-anxiety-disorder

https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/social-anxiety-disorder

https://www.psycom.net/glossophobia-fear-of-public-speaking