The harsh reality of life with an unusual phobia

Guy Baglow, clinical lead at the Mindspa Phobia Clinic, was interviewed in an article about the treatment of unusual phobias

Article by Emine Saner of The Guardian newspaper

21 November 2024

‘I can cope with someone eating one, although I might try to get as far away from them as possible.’

The news that a Swedish politician has rooms swept for the fruit prompted online mockery last week. But for those who face bizarre and irrational fears – from buttons to crumpets – the everyday struggle is far from amusing.

As ever when it comes to bananas, Sarah has been on high alert this week, after the revelation that a Swedish government minister, Paulina Brandberg, has a banana phobia severe enough that aides must ensure there are “no traces” of the fruit anywhere in her vicinity. “We will secure the conference so that there are no bananas,” promised the organisers of one event, in emails leaked to a Swedish newspaper.

While most of the coverage has been mocking, for Sarah, it is entirely understandable – she also has a banana phobia. She is so attuned to the threat that she can sniff out a banana, or a recently consumed one, in a room. “Then, I often have a strong disgust response,” she says. This usually involves feeling sick. “There’s also a hypervigilance, so I’ll be acutely aware of where they are and feel them drawing my attention.”

It wasn’t always the case. Like most babies and toddlers, Sarah loved bananas. Then, when she was about four, she went off them, seemingly overnight. Sarah, a neuroscientist, says she doesn’t remember any “adverse incident”, but adds: “Based on the theory of phobias, one would hypothesise that something had happened, that I’d interacted with one negatively, given it came on so fast.”

Banana-phobe Swedish minister’s staff insisted on ‘no traces in the room’

For those of us who have never interacted with a banana negatively, it can be hard to understand, which Sarah accepts. As a teenager, it was embarrassing, “because it’s a bit more of a comedy fruit”. At university, her housemates would prank her: “They’d hide them in my bed and leave little notes.” She laughs – she is able to see the funny side, even while barely disguising her disgust. “They were my friends; it’s gentle teasing.” At least the bananas were not unpeeled. If it had been a naked banana? “Oh my God,” she says, voice rising. “I can’t even imagine. I’d make them change the sheets.”

These days, Sarah largely has it under control. She can go to the supermarket and steer clear of the bananas, comforted by the fact the store is large and airy. It’s worse in a meeting room with a fruit bowl on the table, a banana squatting menacingly. “I’ll just sit far away from it. I can cope with someone eating one, although I might try to get as far away from them as possible. But when someone surprises me or I can’t escape, I might get more panicky.”

Once, she was on a flight and woke to discover everyone around her had been delivered their morning snack – a banana. Recently, she was on a bus and had to move away from a discarded peel. “Most of the time, you can avoid them. I’ve learned to find tactful ways of removing myself without making it obvious,” she says.

Sarah has published research on ways to treat other phobias, although she has no intention of trying to cure herself. “Even though it’s not necessarily practical to have a banana phobia, the thought of having to go through exposure therapy feels so horrific that I prefer to keep the phobia.” She has a scientist’s interest, though, and has tracked down stories about others with rare phobias. “There seem to be things that you would think are really unusual that come up a bit more prominently than chance – bananas seems to be one of them,” she says. “Buttons is another. It doesn’t seem to be completely random.”

The rational side of our brain tells us we’re being irrational, but we still can’t stop feeling that way

Fear of spiders or snakes is understandable from an evolutionary perspective, she says. With bananas, “I’ve speculated that they have quite a distinctive smell and texture, which seems to be entwined with a disgust response”. Perhaps our survival instinct, she suggests, is to avoid foods that are “mushy”, which might indicate they are rotten.

Sarah knows her banana phobia is odd, although its comic nature brings its own problems (nobody, surely, would put a spider in the bed of an arachnophobe). She doesn’t tend to tell people, even though it affects her. In her professional life, she worries that “it might make me seem ridiculous and less credible” (neuroscience, like politics, is still dominated by men).

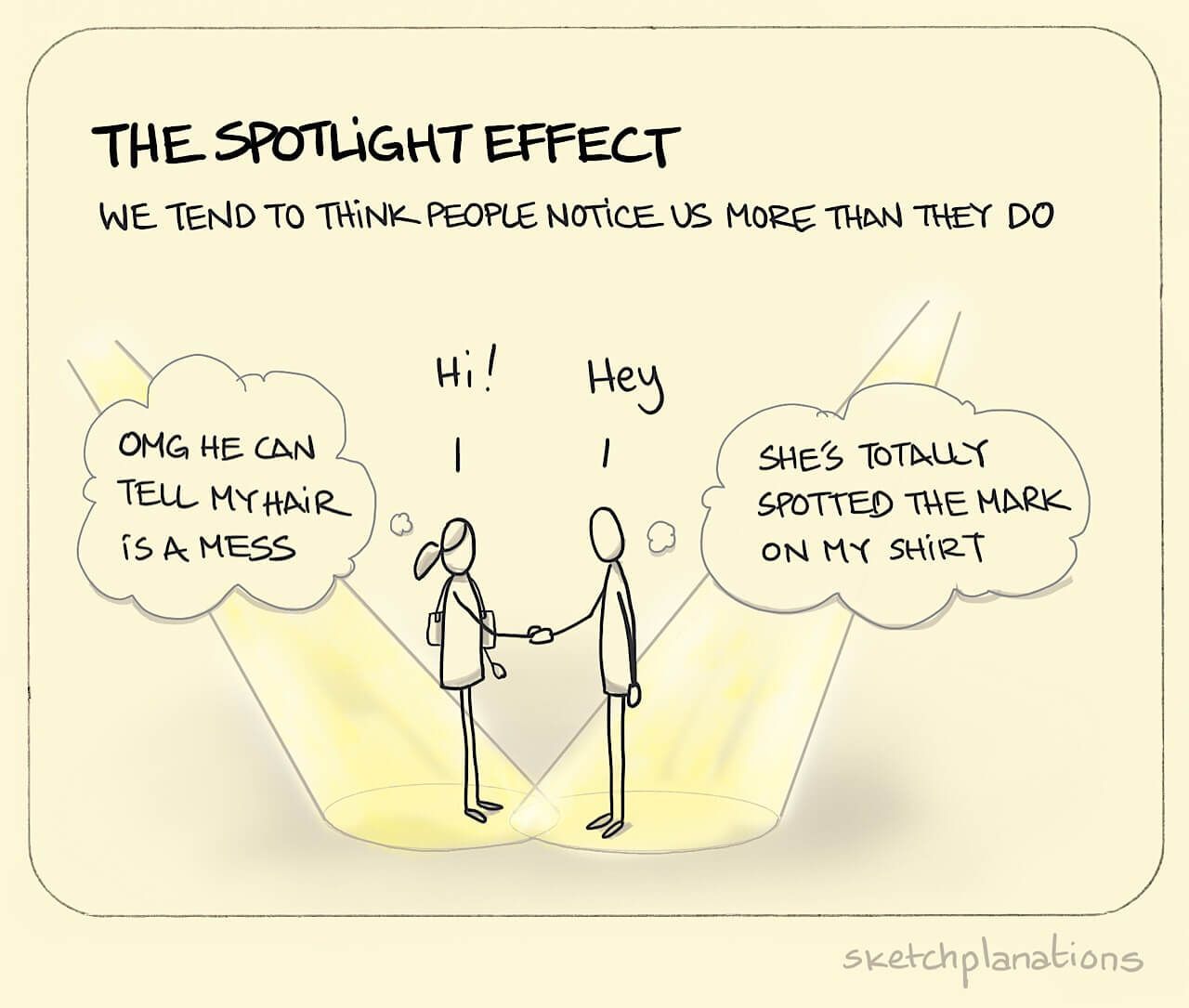

“The rational side of our brain tells us we’re being irrational, but we still can’t stop feeling that way,” says Dave Smithson, a spokesperson for Anxiety UK. Phobias tend to be learned – my arachnophobia probably comes from my mother, who probably got it from her mother, and so on. But they can also develop, at any age, due to trauma.

Smithson says Anxiety UK has a long list of reported phobias: “Things you just never would have imagined – shadows, animal skin, railways, fear of gravity. What would cause that? But it can happen. People have fears about all sorts of things.” What makes it harder for those with more unusual phobias is the fear of being ridiculed. “They don’t talk about it, they don’t seek help. People will organise their lives around not facing that fear.”

Because many people keep their phobias to themselves and few seek treatment, phobias are not a well-researched area of anxiety and their prevalence is tricky to ascertain. The most recent Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey for England, which is 10 years old, found that 2.4% of people had a phobia. In the US, an estimated 12.5% of adults experience a phobia at some point, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

The “medicalisation” of a phobia is a relatively recent concept, says Joanna Bourke, a historian and the author of Fear: A Cultural History. “People have been frightened of things for ever, but ‘phobias’ is a late 18th-century concept,” she says. “Even such a thing as agoraphobia, which is the most researched of all the phobias – the fear of open spaces – is a late-19th-century invention. To some extent, they are culturally constructed. What we are afraid of reflects new technologies, new things in our environment.” Our ancestors may well have been afraid of spiders or heights, but they won’t have had a phobia about air travel.

Kate Summerscale details unusual phobias in The Book of Phobias and Manias. Although clowns have been disturbing for centuries, a phobia of clowns (coulrophobia) is a late-20th-century idea. Summerscale traces it to the conviction in 1980 of an Illinois

serial killer and children’s entertainer, then the popularity of Stephen King’s horror novel It.

Summerscale traces trypophobia – a fear of a cluster of small holes – to an image that spread around the internet in 2003, supposedly showing a maggot-infested breast. It was fake, but plenty of people have expressed their horror of clustered holes in everything from crumpets to, in 2019, the grouped camera lenses on the back of the iPhone 11 Pro. (Evolutionary psychologists have theorised that being averse to clustered holes or bumps could be our warning system against infectious disease.)

People can develop exaggerated fears of things that most of us are frightened of – death, illness – but one theory for specific, unusual fears is that it involves “some kind of displacement from something that’s unconsciously frightening”, says Bourke. An object such as a banana or a ball of cotton wool becomes a stand-in for the underlying fear.

Cognitive behavioural therapy, which can include gradual exposure to the fear, is widely used to treat phobias. Virtual reality has been introduced, too; one study found that “very brief exposure” therapy – so quick that the person isn’t even aware they have seen an image – may work.

Guy Baglow, the clinical lead at the Mindspa Phobia Clinic in London’s Harley Street, uses neurolinguistic programming (NLP) – a way of changing thinking patterns – to disrupt the association between an object and fear. Although NLP, which has been around since the 1970s, has its detractors – who say there has not been enough rigorous evidence for it – Baglow insists it can work quickly for phobias.

In 20 years, he has come across banana phobia only twice, he says. In one case, a woman had, as a child, accidentally electrocuted herself at the same time her eyes fixed on a bowl of bananas. “The bananas got associated with the shock,” he says. “The mind creates patterns so it can avoid things in future that might be dangerous or threatening.”

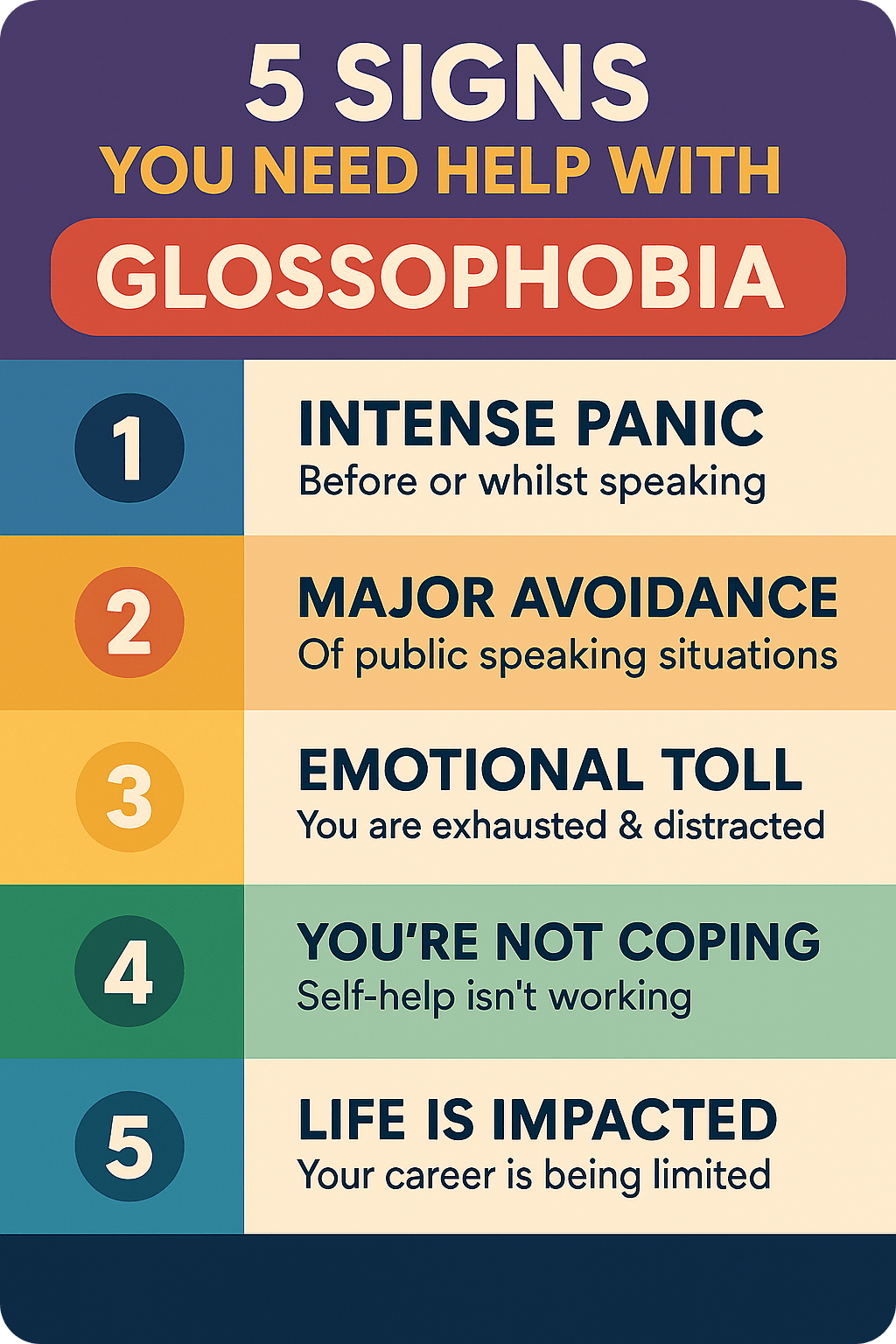

Baglow says one man had a tomato phobia associated with cruelty he experienced in childhood. “You can have a phobia of anything, because trauma can attach to pretty much any object or situation,” he says. “It’s the survival response gone slightly awry.” Phobias can have a significant impact, no matter how ridiculous they may seem to others. “Avoidance, which is one of the key definers of phobia, can lead to all kinds of behaviours and can really restrict people’s lives.”

Avoidance is Keir Gale’s main strategy, although it’s hard – he has a phobia of buttons, which is common enough to have been given a name: koumpounophobia. Buttons, once you start to notice them, are everywhere. “I have to avert my eyes if they’re obvious on

somebody’s clothing,” says Gale. He has had to explain to people why he can’t look at them. What happens when he encounters a button? “I feel nauseous. If I touch one, which you have to do from time to time, I have to wipe my fingers afterwards, because I feel like they’re dirty and greasy and generally unpleasant.” He experiences “a kind of crawling sensation in the skin”. Just the sound of buttons from a shirt or jacket sleeve clattering on a table makes him squirm. “Almost every sensory input is affected.”

He has had what he describes as a revulsion, rather than a fear, for as long as he can remember – his mother would have to remove buttons from his clothing. Gale, who is retired, sometimes had to wear formal clothing for work, which was difficult. These days, he can wear trousers with a button fastening as long as it can be covered by a belt. “Duvet covers have always been a problem and I’ve tried to find ones with poppers. If I think my feet might touch them while I’m in bed, I get very anxious.” Buttons on upholstery are horrifying.

I fit it into my day – I anticipate the amount of extra time it’s going to take me so I don’t have to walk across grass

He is a little embarrassed about it, he says, adding that those who do know “don’t really have any idea how deep the impact is, so they don’t necessarily take precautions”. They don’t ridicule him, but there is certainly bewilderment. “Which is fair enough – I’m bewildered. For them, it’s nothing, but to me it’s very real. My mind won’t let me believe that other people aren’t bothered by them.” He suspects he is neurodiverse and that his phobia is related. I realise that, throughout our phone call, he hasn’t once uttered the word “button”. “I hate it. I don’t like having to say the word.”

Bettina Hunt, an author of romcom novels, has a phobia of grass. “I just don’t like what might be underneath it, like the mud and things coming out of it.” It’s hard to explain, she says – irrationality being central to many phobias – but it’s not merely a fear of dirt or grime. She can tolerate a lush green lawn, perhaps at a stately home, “but I wouldn’t want to walk on it”. The idea of sitting on grass is impossible. “Picnics? Absolute nightmare. I’ll do anything to avoid them. If I absolutely have to, then I will stand up.” She has never walked barefoot on a lawn. She has hated grass for as long as she can remember. She never wanted to go to the park, like other children, and avoided PE at school. Being made to do a wheelbarrow race, on her hands, her face close to the strands, as another child held her feet, remains a visceral and revolting memory. She has a patio, but has never been to the shed at the bottom of the garden, because it involves crossing grass. Hunt lives by a green, which the rest of her family cut across; she takes the long way round. “I fit it into my day – I anticipate the amount of extra time it’s going to take me so I don’t have to walk across grass.”

Polly Barrett has a balloon phobia, which has meant literally running away from the things. “When I see a balloon, I usually start to get really hot and sweaty. My breathing gets quite shallow and fast and I have the feeling of fight or flight,” she says. “Then comes extreme embarrassment, because it’s ridiculous.” Once, she was in a restaurant when someone sat at the next table with a toddler who had a balloon. The more Barrett tried to suppress her rising discomfort, the worse it got: “I ended up bursting into tears and running out.”

Her fear comes from the balloon’s potential to pop – she can’t handle the sight of a balloon waving around, or two balloons rubbing together – and is linked to her other phobia: sudden loud noises. She has experienced this for as long as she can remember. As a child, a noisy boom or loud music could make her burst into tears; even now, a surprising bang, like a car tyre blowing out, can provoke the same reaction.

Intriguingly, Barrett is a musician – her sensitivity to sound is obviously a benefit in making music, even if it comes with the potential for shock. When she works with sound engineers, she tells them she can’t handle the popping or squeaking that comes from tweaking equipment. Friends ensure no balloons are present at the parties to which she takes her children. These days, she is more open about it and people are understanding. “It’s only in the last couple of years that I’ve properly acknowledged and owned it, because for ages I was so embarrassed.” She thinks she should probably do something about it, “because I don’t know what it’s linked to in the rest of my psyche. If I got over this fear, maybe it would give me this whole new lease of life.”

A cause for celebration, perhaps – at which she may tolerate balloons and the popping of champagne corks.